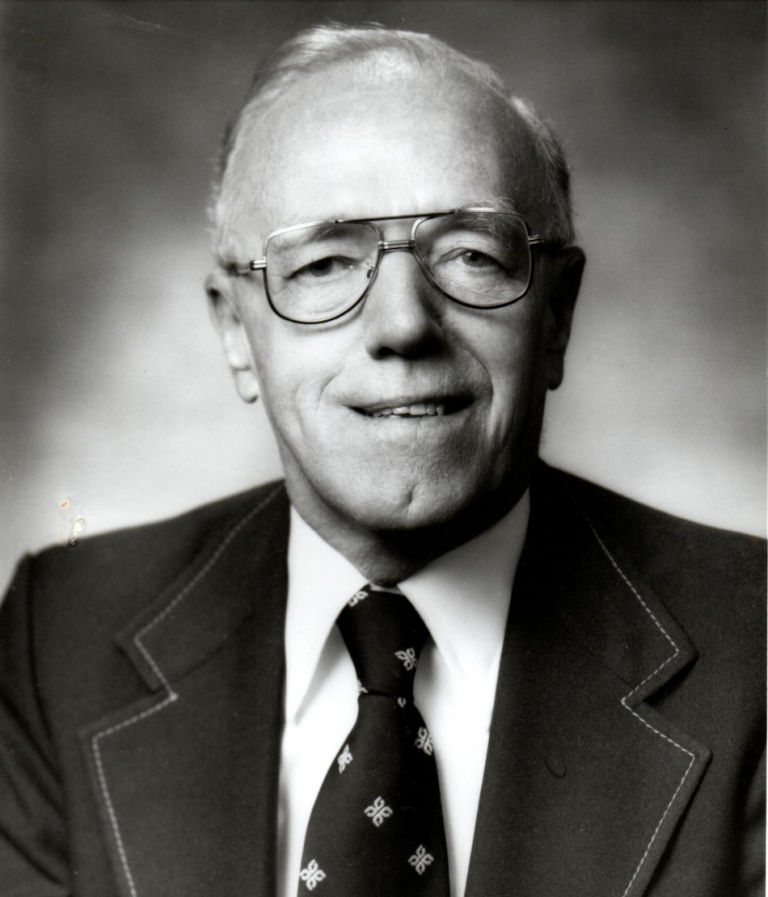

Dr. Kenneth A. Carlson

Minister, First Methodist Church, Glendale, CA

So I Went To Manzanar

A sermon title delivered by the Rev. Kenneth A. Carlson at the Central Methodist Church, Glendale, California, Sunday morning, May 7th, 1944. It provides an “inside” view of life at the Japanese Relocation Center, Manzanar, California during World War II.

Sunday morning, May 7, 1944

I expect there is no problem in all America upon which there has been more heat and less light shed than that of the Japanese situation. The attitudes toward our evacuated Japanese Americans range all the way from fanatical bitterness and hatred to the cynical affirmation that “A Jap is a Jap.”

With very few exceptions the press has accelerated and intensified this feeling until the announcement that one is to speak on the subject brings veiled threats and warnings that he is dealing with “a hot potato.” If anyone ought to be tolerant and understanding, even in the heat of war propaganda, it ought to be one who calls himself Christian. Yet we are finding it difficult to reconcile the so called Christian attitudes of some folk with the mind of Christ , though it is a source of inexpressible satisfaction to know that thousands of Christian men and women have kept their sense of balance and fair play in relation to this delicate Japanese relocation problem.

At this point I am asking you to do something extremely difficult. For some it may require patience, for others the exercise of genuine will power. I am asking you to set aside your prejudices for the next twenty-five minutes. Even forget, if you will, that we are at war. That is not easy to do with sons fighting in the Pacific War area. Dismiss from your mind the propaganda you have read on the subject, and permit me to paint a picture for you solely in terms of human values and human beings.

It is unfortunate that so many Americans see no difference between the Japanese war lords and soldiers who have been trained to kill, and the Japanese who have lived peaceably in our midst for a generation. It is assumed that there is inherent in the Japanese character an element of distrust, sadism and brutality that is not to be found in any other race. This assumption, of course, is based upon propaganda or the statements of so called experts, rather than upon the testimony of science. Anthropologists have long said that there is no basic differences between races, that the 1,000 most brilliant men in the world would include representatives from every race and creed. It is assumed that God put something vicious into the Japanese character that is found nowhere else. Do not misunderstand, I am offering no defense for Japanese militarism, brutality or sadism. The thing I am saying is that this is a product of training and environment, and is no more true of every Japanese than it is true that every American is a criminal. Kagawa has long been recognized as one of the world’s outstanding Christians. Our enemy has taken great pains to understand us. It is now our task to understand him if we are to win the war as well as the peace.

The history of Japan is one of a Feudal System in which the chief end of man has been loyalty. The emotions that other people discharge in occasional anger, grumbling and brawling, the Japanese people store up and discharge all at once. There is very little in Japanese life, in Japan, that permits the harmless diffusion of emotion; rather, everything locks it in, represses it, frustrates it, and chokes it. For instance, it is poor taste in Japan to disagree with someone else’s ideas, it is good taste to agree and to keep your thoughts to yourself. Life is weighted down with the precise observance of ceremonies, and one must continually honor those of higher social standing or caste, thus the Japanese people have very little opportunity for self-expression, simply because they do not exist as individuals at all. They exist only as a family unit as an object of loyalty to the state. The entire social fabric goes back to Confucius who said that younger sons should obey older sons, that sons should obey their fathers, and fathers their fathers. The psychologist will tell you, then that the very simplicity and severity of Japanese life seem to be the forces that produce such powerful explosions of pent-up emotion. Men who carry themselves with dignity when sober, go mad when drunk. War likewise provides an outlet for this emotion. It intoxicates the mind so that disciplined soldiers will go berserk when put on their own and commit atrocities that stagger the imagination. Mr. H. G. Bouvenkirk, our host at Manzanar, spent 16 years in Japan as a Missionary for the Presbyterian Church. He was on a boat heading for America when Pearl Harbor came. The ship returned to Japan and Bouvenkirk was imprisoned. He was transferred from one prison to another and says that it is not possible to generalize concerning Japan’s treatment of prisoners of war. In one prison the treatment is fine. In another fair, in another bad, depending upon the personnel and their background experience.

This is likewise true of the Philippine camps. Poor conditions in one camp may be counteracted by gracious treatment in another. Mr. Bouvenkirk stated that the common people of Japan are beginning to break the strange hold of this Feidal System and its controlling war party. Thousands of common people in Japan are as horrified over Pearl Harbor as we were, which is the reason they have smuggled food, etc. to American prisoners of war in pain of death. I have been undertaking to say we must not be blinded by sheer prejudice to the fact there are many good, yes Christian, people in Japan, just as there are in Germany and Italy. If when Japan is defeated, we can help these people to do away with the Feudal System and change the character of the nation’s educational system, life, liberty, and happiness will be within reach of the common man. And a generation or two from now we shall find a national character in Japan comparable with our own.

In 1861 there was one Japanese in America. It was not until 1880 that Japan permitted the migration of her people to America. By 1898, 2,000 had come in response to a west coast labor need, by 1900 this number had increased to 10,000. They were, of course, received with open arms, though the first anti-Japanese book was published in 1901. During the First World War there was absolutely no resentment against the Japanese here since Japan was our ally. Following the war pressure groups began their work, resulting in the Exclusion Act of 1923. The American Legion, since its founding in 1919, has never once failed to pass an Annual

Resolution against the Japanese Americans, according to a most illuminating article in the April issue of Fortune Magazine. Says Fortune, “It did not require a war to make the farmers, the legion, the native sons and daughters of the golden west, and the politicians resent and hate the Japanese Americans.” For decades the Hearst Press has campaigned against the “Yello Peril” within the state—one percent of the population. When war came Hearst’s campaign of hate and fear broke all bounds. The motive behind this has been largely economic, as the Japanese grew vegetables on $70 million dollars’ worth of California land, thus competition was keen.

Since 1818 a generation of Japanese has grown up in America which knows no ideology loyalty to Japan. They have grown up in a Democracy, not a Feudal System. Their education and environment has been different from that of their ancestors. A friend high in the Consular Service tells me that one of Japan’s greatest disappointments of the war has been in the fact that the Japanese Americans did not rise up to paralyze the war effort on the Pacific Coast. Someone says, “Well, we didn’t give them the chance.” The fact is, we did. It was not until March 29th, 1942 that our 110,000 Japanese Americans were herded into Assembly Centers. Within 24 hours after Pearl Harbor, Richard B. Hood, FBI Chief for this area, tells me 3,500 potential Japanese sabateurs had been rounded up, largely in the terminal island area. These imprisoned were Japanese language school teachers commercial representatives and Government employees. The personal history of every one of the 110,000 Japanese was personally known to the FBI. 106,000 were judged to be loyal. The fact that not a single act of sabotage was committed on the west coast prior the evacuation in March indicates the FBI knew what it was doing. Of the 3,500 locked up a considerable number had criminal records. 106,000 Japanese Americans knew but one loyalty—THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

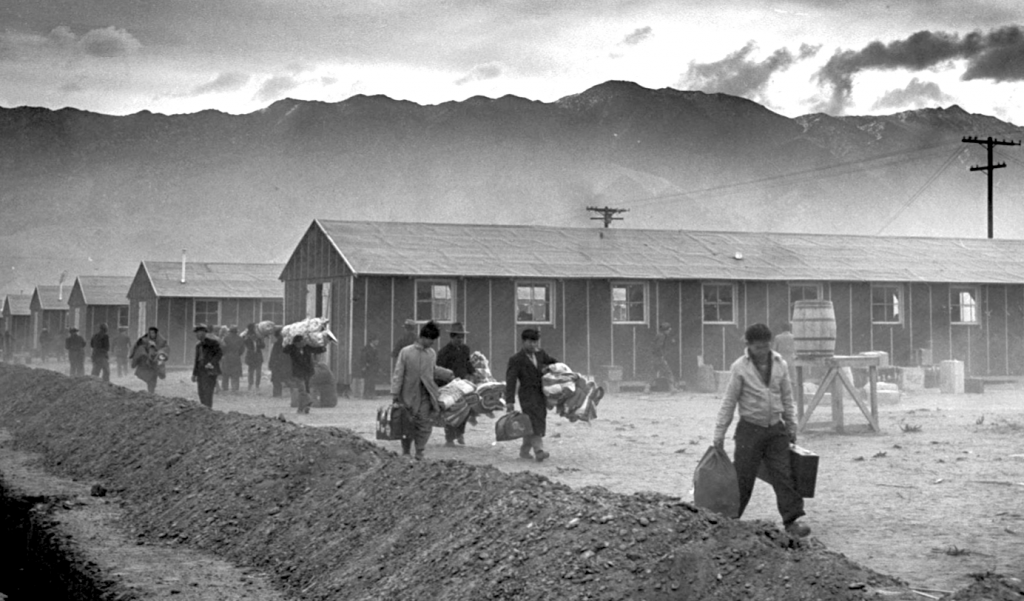

The army, in 28 days, rigged up primitive barracks in 15 assembly centers to provide temporary quarters. Each evacuee made his own mattress of straw, took his place in the crowded barracks, and tried to adjust to the new life. A civilian agency, The War Relocation Authority was created, whose job was to hold the people until they could be relocated in orderly fashioned. The WRA has taken a terrific beating for thus far having relocated 17,000 Japanese through the midwest and east. In doing so it is fulfilling the function for which it was created. Of the 17,000 thus far released, not one has been convicted of Anti-American activity. Under the pressure of the Hearst and other papers, the general public has closed its eyes to these facts. The DIES Committee has fumed at the WRA. Herman Eberharter, a member of the DIES Committee said of its report, “It is prejudiced and most of its statements are not proven.” The committee wound up by suggesting three policies, all of which the WRA had already adopted. The committee accused the Manzanar Center of pampering the internees. To this day not one member of the DIES Committee has set foot within the Center.

At first, the internees were very bitter over their loss of land, homes, money, and freedom. They knew that German and Italian aliens had not been locked up; in fact, the Japanese in other sections of the United States had not been locked up unless the FBI had reason to suspect them. This bitterness has largely been supplanted by a hope for the future. Rev. Seiya Sakai, former pastor of the Japanese Church across the street from us, expressed the sentiment of many when he said, “My people now realize that this is a product of war. As Japanese it was to be expected that something like this would happen to us. We are not complaining. We believe in America’s sense of fair play and justice and are living for the future.”

Manzanar is one of nine relocation centers. Like the others it is a tiny square in the midst of a lonely desert valley. The breath-taking Sierra Nevada Mountains are to the west. Said Mr. Sakai, “When we first came here and were discouraged, we lifted our eyes unto the hills and from there came out strength.” At present there are 6,000 internees at Manzanar, some 1,200 having been already relocated from this Center. Miss. Nogohama, one of the girls from our neighboring church, is to enter our Methodist Kansas City Training School in two weeks.

Those who have been relocated are primarily young people, the older folk are more reticent about leaving the Centers. There are several reasons: 1. Having lost everything, it isn’t easy to begin life anew in a strange town. 2. The resentment of public opinion would make normal living difficult. 3. The Centers provide security for the present, at least, so why leave security for uncertainty. Those who leave the center are fortified with official papers, a numbered identification card bearing picture and fingerprints. They get their railroad fare, $3 a day travel money, and if they have no savings receive $25 in cash.

It takes courage to face a society that rejected you two years ago. The Center bulletin board lists many attractive jobs in the Midwest and East. Illinois has taken more relocated Japanese than any other state—4,000 of them. In Winnetka and other suburbs housewives compete for NE IS I Servants. Others find their way into professions. When they write back, “we can eat in any restaurant in New York,” or “in Chicago nobody seems to care that I have a Japanese face,” others are encouraged to try their luck in the outside world. Tacked to the bulletin board is this notice from the Etheopian Selective Service: “Married men may bring wives to cook for them. Men without wives bring any available women with them. Anyone found at home would be hung.”

These young folks have not lost their sense of humor. A lot of so called Patriots are fretting over the eventual return of the Japanese to this area. The fact is it appears now that not much more than 1/3 of these people will want to return here. One beautiful young Japanese American, a high school graduate, put it this way, “In the Midwest and East we are finding professionals open to us that denied us entrance in California. Here we have been a servant people, gardeners and laundry workers. At the close of the war why should we turn our back on these promising careers to again become laundrymen in California.” The Glendale Japanese Americans do not anticipate enough of their people will want to return here to warrant the continuance of their Christian Church, thus they are seriously considering selling the property.

The WRA Administration, according to Mr. Bouvenkirk, has been amazed at the basic honesty and frankness of these people. That’s a statement you won’t hear very often in these war days. I came away tremendously proud of the fine job the WRA is doing in rehabilitating these people. Most of the staff consists of Caucasian leadership. Every able bodied man must work, also women if not hindered by family responsibilities. Many industries are represented. There is a shoe shop, clothing manufacturing and reconditioning division, barber shop co-op store, etc. We watched them make TOFU, which is a favorite Japanese delicacy, made from the milk of the crushed soy bean. From the residue of the bean a soy sauce is made, and the combination is delicious. (PS—Anyone here can have my share). It is made daily from 4 to 8 a.m., though not all mess halls serve it on the same day.

We also watched them make mattresses. California grown cotton is used and is blown into the mattress. I was gazing through the blower funnel when our guide decided to illustrate how it works. Ten seconds later I looked like a mattress. Also, there is a government experimental station, operated by Japanese Americans, for Guayle, the widely publicized rubber plant. A most interesting piece of work is being done at this point. The maximum wage is $19 per month. This would be a doctor’s salary. The minimum is $12, and the average $16. There is a clothing allowance of $3.75 per month for each adult. Medical care and meals are provided by the Government. Lest this sounds too attractive, imagine a doctor, distinguished in his profession who lived with comfort before the war, now huddled in a small room with his family and serving under a Caucasian of lesser ability.

The people are jammed together in frame barracks. A family of seven has an “apartment” (one room) which would measure about 20 by 25 feet. It is a bare room, without partitions. Your only privacy from the next family is achieved by hanging a flimsy curtain between the crowded beds. Furniture is improvised from bits of scrap lumber, and a box is used for a table. Young children do not get proper rest at night because of this lack of privacy, thus there is considerable restlessness among the youngsters. It creates a problem for the school teachers.

There is no running water in the barracks, no cooking facilities or toilet facilities. If one is fortunate enough to have an electric plate he can cook on the side. In spite of the unending wind and dust, the barracks are spotless, typical Japanese cleanliness. Clothes are stuffed under the beds, or on shelves if scrap lumber is available. Run off water from the nearby mountains has been utilized, thus irrigation has made possible attractive lawns, and a beautiful little park in the center of the camp. It is remarkable what these people have been able to do with practically nothing.

The hospital facilities are quite complete and new equipment is being added as time goes on. We were fascinated by the children. Kids are kids whatever the race may be. It is pretty difficult to look into the face of these lovely little ones and think all the mean things abut them that you read in the papers. We visited a young lad who was isolated from the rest. Asked him what the trouble was, and he grinned, “Measles!” (We made a hasty retreat!). The children’s village for orphans houses 52 young people at present, ranging in age from a few months to 17. Orphaned youngsters are brought here from other centers. The brilliant young Japanese American in charge expects to join the staff of the Children’s Bureau at Washington shortly. Oil heat is used throughout the Center.

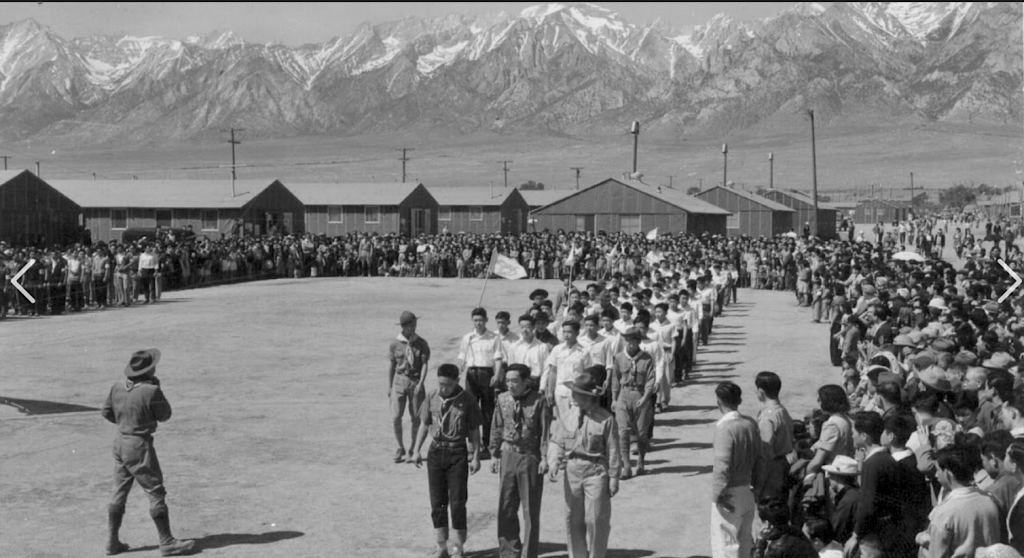

Many activities are planned for the evacuees, planned by the administration and Mr. Bouvenkirk, who is stationed there by the Presbyterian Church. The activities include sports, forums, paneled discussions, night school courses, hobby interests and so on. The night we were there a panel discussion was held between two Caucasians (members of the staff) and two fine Japanese Americans. The discussion topic was, “The Japanese in America.” It traced the history of the people here, with particular emphasis upon the adjustment that is taking place in family life. The adjustment in family life is perhaps the most important transition that is now taking place in the Center. Of this we will have more to say next Sunday in relation to our family Sunday theme. Also, I will give you an insight into the Tule Lake situation, which likewise is clearly identified with the family pattern.

The museum contains a display of the creative genius of these people. Here one will find inspiriting examples of what can be accomplished when individual initiative is encouraged as it is here in America. Articles of every kind and description are to be seen. One budding genius decided to illustrate posture—good, bad, and medium, via pictures and poetry.

Under the first picture one reads:

“First with slinky backward crouch,

Enters Debutante Sylvia slouch

Up with hips and down with seat

Here is Sylvia all complete

Saggy shoulders and sunken chest

Poor old diaphragm quite depressed

Who is Sylvia? She’s a sight.

I can say to you very honestly that no one who has visited a Relocation Center, seen the living space and eaten the food could apply the word, “Coddling” to the WRA’s administration of the camps. We ate our meals with the evacuees. I took a box of oranges to the Christian folks. How grateful they were, since fruit is scarce at this time of the year. We were guests of the Christian colony for dinner Tuesday night. Mrs. Sakai set a tray of oranges in the center of the table that all might share. For dinner we ate rice, fish, a vegetable called gora, soya sauce, and tea. The next noon we ate rice, a chow mein mixture, cabbage salad, soya residue, bread, tea, and an apple. The food is adequate though monotonous. However, the Japanese Americans think the food is o.k. As one girl put it, “The food is satisfactory. It’s the way it’s prepared!”

The cooks are of the older generation Japanese and stick to the old traditions in food preparation, which doesn’t click so good with the younger folks. It isn’t tasty or appetizing, with little variation in the menu. There is very little sickness in the camp, which indicates that the food is nourishing. The “luxury” meals you’ve read about just don’t exist. There is no butter at any time. Oleo margerine is served for breakfast only. Milk is available for youngsters only, when it is available. We went through the refrigeration department where the fresh meat is kept. The Caucasian staff, Officers and Military Police, enjoy Grade 1 meats, while the Japanese Americans get from grade 3 to 6. Meat that is fit only for stewing. All told the food is close to the edge of decent nutrition. Some 1/3 of the food requirements are grown on the 350 acres under irrigation at the Center, thus reducing the actual cash outlay for food to 31 cents per day per person.

And so life goes on within the Relocation Center. I think it can be honestly said that many people here are enjoying a social life and educational opportunity that they have never known before. This in spite of the fact that not one of us here this morning would care to change living conditions with them. In fact, according to Mr. Bouvenkirk, the only real prisoners are the Military Police. They are stationed outside the Center and separated from everything and everyone. They are isolated from civilization. It is ironical that these who are the guards should be the real prisoners. No one has ever sought to escape from the Center. Manzanar is looked upon as the best of the Relocation Centers, and certainly this is far from ideal, considering the effect upon family life which we shall consider next week.

That this is and will be America’s most pressing problem is beyond question. Likewise, as far as the FBI, WRA and ARMY are concerned the loyalty of these remaining at the Center is unquestioned. The young men are now being drafted into the Army. For instance, you will find here the Japanese Americans who boycotted the Japanese Embassy in San Francisco when the Nanking incident became known. Here are the young men and women who day after day boycotted the San Pedro and San Francisco docks when “good Americans” were shipping scrap metal to Japan. These Japanese Americans protested with all their souls. A brilliant young man, who was a member of the Inglewood Chamber of Commerce, one of the most respected members of that organization, said, “I have always been an American and will always be an American. I know no other loyalty.”

It is time, then, that Christians begin to think intelligently and sympathetically concerning the human values at stake here. Permit me to close with a thought provoking statement from an article in the April issue of Fortune Magazine, already referred to: “When future historians review the record, they may have difficulty reconciling the Army’s policy in California with that pursued in Hawaii. People of Japanese blood make up more than 1/3 of the Hawaiian Island’s population, yet no large scale evacuation was ordered after Pearl Harbor and Hickman Field became a shambles. Martial Law was declared. The Department of Justice and military authorities went about their business, rounded up a few thousand suspects. In Hawaii, unlike California, there was no strong political or economic pressure demanding evacuation of the Japanese Americans. Indeed, had they been removed, the very foundation of peace time Hawaiian life, sugar and pineapple growing, would have been wrecked. General Delce C. Emmons, who commanded the Hawaiian district in 1943 (and now commands our Western Defense Command) has said of the Japanese Americans there: “They added materially to the strength of the area. By continuing to keep American citizens in “protective custody” the U.S. is holding to a policy as ominous as it is new. The American custom in the past has been to lock up the citizen who commits violence, not the victim of his threats and blows.”

To sum it up in the words of one splendid Japanese American at Manzaner, “We have been here for two years now. We have adjusted ourselves to what probably was a necessity. We hold no bitterness toward anyone. We believe America’s sense of justice will do for us that which is right. We do not ask to return to California cities now, but we pray we shall not be denied that right at the close of the war.”

Let us pray God that this young man and the others like him will realize this great hope.

The end

Dr. Carlson went on to have a distinguished career, which included 12 years at the Santa Monica First Methodist Church before returning to Glendale for 16 years at the Glendale First Methodist Church. Known for his powerful preaching, a weekly radio broadcast and public speaking outreach, during his tenure he built each church into “the largest west of the Rocky Mountains”.

Copyright 2022. All rights reserved.